Why Language Training Matters for South Asian Studies:

Back To Blogs

Why Language Training Matters for South Asian Studies:

Arihanta Institute’s Commitment

02/16/2026

Language Training is Essential, Not Merely Optional

South Asian language studies are not optional for serious scholars of South Asia—they are foundational. Whether one approaches the region through anthropology, sociology, philosophy, theology, or history, language competency is indispensable. Without it, scholars risk producing research that is detached from the lived realities, textual traditions, and interpretive depth of the cultures they study.

South Asian language studies are not optional for serious scholars of South Asia—they are foundational. Whether one approaches the region through anthropology, sociology, philosophy, theology, or history, language competency is indispensable. Without it, scholars risk producing research that is detached from the lived realities, textual traditions, and interpretive depth of the cultures they study.

In an era when disciplinary boundaries are increasingly porous, language training allows scholars to cross those boundaries with integrity. Ethnographers cannot rely solely on English-speaking interlocutors or mediated translations. Philosophers cannot depend on others’ renderings of Sanskrit or Prakrit texts without compromising the rigor of their own interpretations. Historians, likewise, cannot piece together nuanced cultural narratives without access to sources written in local vernaculars or liturgical languages. Simply put: language study is not ancillary to South Asian studies—it is the key that unlocks the field.

The Social Sciences: Language as a Gateway to Communities

For scholars working in anthropology, ethnography, sociology, and related social sciences, language is the medium of authentic human encounter. South Asia’s rich cultural diversity cannot be understood from the outside looking in. Fieldwork requires not only conversations with living communities but also engagement with the religious and cultural texts that inform those communities’ worldviews.

For scholars working in anthropology, ethnography, sociology, and related social sciences, language is the medium of authentic human encounter. South Asia’s rich cultural diversity cannot be understood from the outside looking in. Fieldwork requires not only conversations with living communities but also engagement with the religious and cultural texts that inform those communities’ worldviews.

A sociologist interviewing a Jain community leader, for instance, will almost certainly encounter references to scriptural texts or traditional philosophical frameworks. To interpret those references responsibly, the scholar must have at least a working knowledge of the relevant liturgical languages. Even in cases where a community primarily uses a modern vernacular such as Gujarati, Hindi, or Bengali, the underpinnings of cultural self-understanding are frequently grounded in Sanskrit or Prakrit texts. Without this linguistic preparation, the ethnographer risks missing the deeper context that gives meaning to local voices.

The Humanities: Access to Primary Texts

For scholars approaching South Asia through philosophy, theology, ethics, or literature, the stakes are even higher. These disciplines rely directly on close readings of canonical and classical texts. Here, translations provided by others are simply not enough. Every translation involves interpretation—sometimes subtle, sometimes overt. Philosophical nuances often hinge on fine distinctions of grammar or on polyvalent terms that resist simple English equivalents. Even novice scholars will notice that words like dharma, ātman, or ahiṃsā carry connotations that cannot be flattened into a single translation without losing layers of meaning. Scholars relying exclusively on translations risk misrepresenting the very traditions they aim to study.

Moreover, artificial intelligence has introduced new tools for translation, but these are of limited value without human expertise. Machine translations may provide a rough approximation, but they cannot substitute for a scholar’s trained sensitivity to context, genre, and textual tradition. Rigorous philology remains irreplaceable.

Thus, scholars in the humanities in South Asian studies must ground themselves in liturgical languages such as Sanskrit, Pāli, and Ardhamāgadhī, as well as in vernaculars like Gujarati, Hindi, or Tamil, depending on the communities they study. For Jain studies in particular, Ardhamāgadhī and Sanskrit are indispensable, but so too is Gujarati, the language of many modern Jain communities and texts.

The Competitive Academic Landscape

The academic job market in South Asian studies is highly competitive. Graduate students and early-career scholars must distinguish themselves not only through innovative research but also through demonstrable expertise. Robust language training is one of the clearest ways to do so.

When presenting at conferences or submitting manuscripts for peer review, scholars with strong language skills stand out. Reviewers notice when a scholar produces their own translations rather than relying on secondary sources. Such work signals not only linguistic competence but also deep engagement with primary materials. It demonstrates a level of credibility and authority that is essential for scholarly reputation.

In publications, philological precision can make the difference between an article that advances the field and one that fails to gain traction. Producing one’s own translations shows mastery of the sources and provides new insights that enrich academic discourse. This is why language training is not simply an academic formality—it is a professional necessity.

Beyond Native Fluency: The Need for Academic Philology

Even for those who grow up speaking a South Asian language, academic training is indispensable. Conversational fluency does not automatically translate into philological expertise. Academic work requires precise translations, grammatical analysis, and sensitivity to historical shifts in meaning.

Philology is more than translation; it is a method. It demands rigorous attention to linguistic structure, etymology, and textual context. It equips scholars to produce careful interpretations that meet the highest academic standards. Community-based learning or informal exposure to a language, while valuable, does not typically provide the depth of training required for scholarly publication. This is why formal language instruction—rooted in grammar, syntax, and close reading of primary texts—is essential for all serious scholars of South Asian traditions.

The Current Challenge: Diminishing Access to Language Training

Unfortunately, while the need for rigorous language training is greater than ever, access to such training is diminishing. Across the humanities and social sciences, funding is shrinking, and many universities are reducing or eliminating their language programs. South Asian languages, already underrepresented, are often the first to be cut.

Paradoxically, interest in South Asian studies remains strong, and fields such as Jain studies are even experiencing growth. Yet the infrastructure to provide essential language training is under increasing strain. This creates a gap between student interest and institutional support—a gap that Arihanta Institute is determined to address.

Arihanta Institute’s Response: Rigorous, Accessible, Online Language Programs

At Arihanta Institute, we are developing innovative, academically rigorous programs to make South Asian language training more widely accessible. Our model combines the best of traditional philological instruction with the flexibility of online learning. Through synchronous classes, students and scholars from across institutions—or qualified students not affiliated with an institution—can participate in live, interactive language instruction, regardless of their physical location.

Our courses emphasize not only linguistic competency but also the academic methods necessary for responsible scholarship. Students learn to read texts carefully, translate them with precision, and situate them within broader cultural and philosophical frameworks.

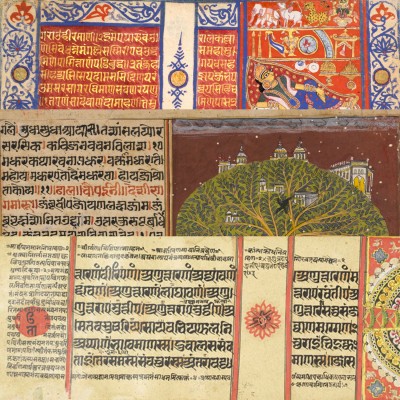

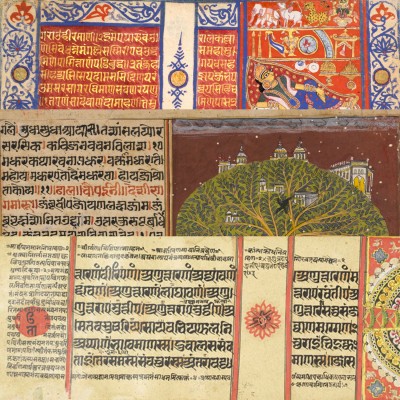

Currently, Arihanta Institute offers courses in Sanskrit and Modern Gujarati, with plans to expand to Ardhamāgadhī and additional Prakrits. We have also offered training in Pāli, recognizing its central importance for Buddhist studies. Each of these languages plays a crucial role in South Asian and Jain studies: Sanskrit is the classical language of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, essential for philosophy, theology, and literature. Ardhamāgadhī is the primary language of the Jain canon, foundational for serious study of Jainism. Pāli is the canonical language of Theravāda Buddhism, indispensable for Buddhist studies. Gujarati is both a modern vernacular and a key language of contemporary Jain communities, as well as the language of important modern texts.

By offering these courses, Arihanta Institute equips students and scholars with the tools they need to thrive in competitive academic environments while honoring the integrity of the traditions they study.

Expanding Opportunities for Scholars Worldwide

Our goal is not simply to teach languages but to expand opportunities. Many scholars find themselves at institutions that do not offer the South Asian languages most relevant to their research. Others may have some training but require additional coursework to reach a professional level of competence. Still others may find that online access is the only way they can realistically pursue such training, given personal or institutional constraints.

Arihanta Institute’s programs are designed with these scholars in mind. By providing high-quality, accessible instruction, we hope to strengthen the field of South Asian studies as a whole. Language training is not a luxury; it is a necessity. And we are committed to ensuring that necessity is met.

A Word of Personal Commitment

As someone who has devoted my career to the study of South Asian traditions and langauges, I speak not only as an educator but also as a lifelong student of these languages. My own training has taken me from undergraduate study in Asian history to advanced graduate work in Sanskrit and Pāli, and eventually to doctoral research in Hindu and Jain philosophy. Along the way, I have studied at institutions such as the University of California at Berkeley and the Graduate Theological Union, as well as through intensive research trips to India.

I have been fortunate to teach Sanskrit, Pāli, Gujarati, and courses on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain philosophy at a variety of institutions, including Claremont School of Theology, the Graduate Theological Union, and Arihanta Institute. My research has spanned topics from ecological ethics in Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism to contemplative traditions in Jainism, and I have sought to contribute to the field through both scholarship and teaching.

Yet what has remained constant throughout my journey is a simple truth: every breakthrough I have made has been made possible through language study. Without the ability to read texts in the original none of my scholarship would have been possible. It is out of this conviction that I am committed to building programs at Arihanta Institute that provide others with the same opportunities. I know from experience how transformative language training can be—not only for academic careers but for personal growth and understanding. My hope is that Arihanta Institute can serve as a bridge for future generations of scholars, ensuring that the study of South Asian traditions remains as vibrant and rigorous as the traditions themselves deserve.

Conclusion

The future of South Asian studies depends on language training. Without it, scholars cannot access the sources, communities, and traditions that make the field meaningful. Yet at a time when access to such training is diminishing, Arihanta Institute is stepping forward to fill the gap.

By offering rigorous, accessible, online courses in Sanskrit, Gujarati, Ardhamāgadhī, and Pāli, we are equipping scholars with the tools they need to thrive. More than that, we are reaffirming the principle that authentic scholarship begins with respect for language—the medium through which traditions speak.

As we continue to develop these programs, we invite students, scholars, and lifelong learners to join us. Together, we can ensure that the next generation of South Asian studies is not only possible but flourishing.

For those ready to move from principle to practice, our upcoming University Sanskrit 1 & 2 Summer Intensive offers a direct pathway into rigorous language training.

Taught by Professor Bohanec, this accelerated, eight-week sequence integrates a full year of university Sanskrit into one immersive summer experience—building the grammatical and translational foundation needed to begin engaging primary texts with confidence and precision. Designed for serious students and scholars, the course supports those preparing for advanced research, strengthening philological skills, or fulfilling formal language requirements. Learn More.

Cogen Bohanec, MA, PhD holds the position of Assistant Professor in Sanskrit and Jain Studies at Arihanta Institute where he teaches various courses on Jain philosophy and its applications. He received his doctorate in Historical and Cultural Studies of Religion from the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) in Berkeley, California where his research emphasized comparative dharmic traditions and the philosophy of religion. He teaches several foundational self-paced, online courses based in Jain philosophy, yoga, ecology, languages, and interfaith peace-building.

_71771_orig)