The Yoga of Haribhadra Yākinīputra's Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya

The Yoga of Haribhadra Yākinīputra's Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya

In a previous article, I discussed the hagiography, history, and contents of Haribhadra Virahāṅka’s Yogabindu. Here I will discuss these dimensions as they relate to Haribhadra Yākinīputra's text, the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya.

Like Haribhadra Virahāṅka, it is not entirely clear who Haribhadra Yākinīputra was, and whether the Haribhadra who wrote the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya was in fact Haribhadra “Yākinīputra” (“the son of Yākinī”).

Who is Haribhadra Yākinīputra?

The late Paul Dundas wrote an excellent article on “Haribhadra” in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Jainism wherein he explained the evidence we have for the two “Haribhadras,” that is, “Virahāṅka” and “Yākinīputra” (Dundas 2020).

As Dundas relates, the hagiographical narratives of Haribhadra Yākinīputra suggest that he was an overconfident Brahmin priest in his youth who boasted that he would become the disciple of anyone who could propose an intellectual idea that he could not himself explain. One day, however, in a town called Citrapura (in today’s Rajasthan), Haribhadra heard the nun Yākinī reciting Jain teachings. Because he cannot explicate the teachings, and true to his word, Haribhadra takes initiation from the preceptor of Yākinī’s ascetic order. Initially inspired by Yākinī’s chanting, Haribhadra took the name “Yākinīputra,” “the son of Yākinī.”

What happened after Haribhadra Yākinīputra’s initiation is difficult to trace in the hagiographical narratives, as Dundas also points out. In fact, we only have one short account from Haribhadra’s post-conversion life in the colophon of a Jain manuscript:

This is the work of the teacher Haribhadra, an intellectually inadequate person, a follower of the words of the Śvetāmbara teacher Jinadatta who is the ornament of the Vidyādhāra Kula, and son of the nun Yākinī in respect to religion (as cited in Dundas 2020).

As Dundas informs us, the Vidyādhāra Kula is a reference to a mysterious and now nonoperational renunciant order for which we have little historical records (ibid). Beyond this reference, it is not possible to further construct Haribhadra’s hagiographical narrative with much precision.

The historical records are also unclear on whether Haribhadra Yākinīputra and Haribhadra Virahāṅka were two distinct historical figures, since various forms of sometimes conflicting evidence for two distinct Haribhadras emerged in the early twentieth century in the work of Muni Jinavijaya, in the mid-twentieth century in the work of Robert Williams, and in other evidence Dundas presents from the historical record (ibid). The evidence, though certainly not conclusive, presents two Haribhadras: Haribhadra Yākinīputra who lived in the eighth century CE, and Haribhadra Virahāṅka who had written approximately two centuries earlier in the sixth century CE.

For simplicity’s sake, I will follow the scholarly convention to tentatively ascribe the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya to the eighth century CE figure, Haribhadra Yākinīputra.

Haribhadra Yākinīputra’s Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya

Haribhadra Yākinīputra wrote two yoga texts, the Yogaviṃśika (“20 verses on Yoga”) in Prakrit and the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya (“Collection of Views on Yoga”) in Sanskrit. Both texts were skillfully translated into English by K.K. Dixit in 1970 with much attention to the text’s philosophical nuances. Dixit’s translation of the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya contains 228 verses presenting three, eight-fold yogas and one, three-fold yoga.

At the beginning of the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, Haribhadra lays out a three-fold yoga showing tantric influence, which includes:

1) icchā: “desire” to enter path of yoga

2) śāstra: willingness to follow “scriptural knowledge”

3) sāmarthya: “capacity” to take up yoga practices, wherein non-attachment arises spontaneously, and the yogin moves through the world unaffected

(Dixit 1970, v. 3-5)

Following this three-fold yoga, Haribhadra spends more time discussing three, interwoven eight-fold yogas with influence from Patañjali’s Yogasūtra, Vedānta, and Buddhism. Haribhadra names each of the eight parts of the yoga systems as a yoga-viewpoint (yoga-dṛṣṭi). The eight yoga-viewpoints, in order, are:

1) mitrā (friendly)

2) tārā (protector)

3) balā (powerful)

4) dīprā (shining)

5) sthirā (firm)

6) kāntā (pleasing)

7) prabhā (radiant)

8) parā (supreme)

(cf. Dixit 1970, v. 13).

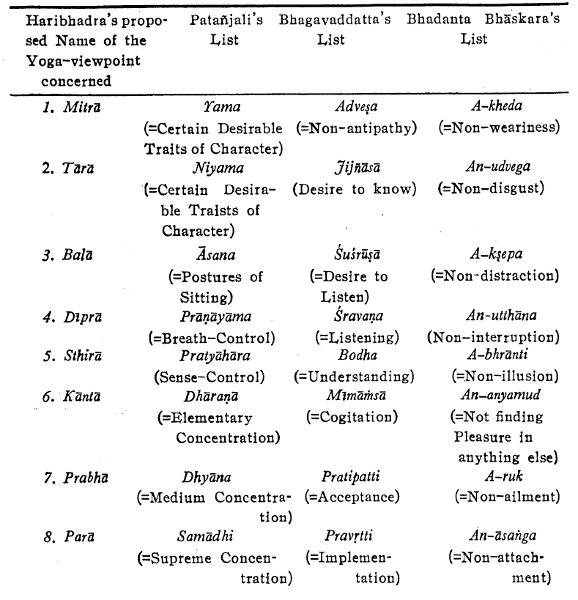

In 1970, K.K. Dixit created an outstanding chart summarizing these viewpoints and the corresponding limb to which each relates in each of the three other systems from Patañjali (Yoga), Bhagavaddatta (Vedānta), and Bhadanta Bhāskara (Buddhism):

(Source: Dixit 1970: page 27)

Haribhadra broadly divides the eight yoga-viewpoints into two sets comprised of the first set of four (1-4 above) and the second set of four (5-8 above). Viewpoints 1-4 are unstable and “liable to degenerate” while viewpoints 5-8 are superior, stable, and not subject to degeneration (Dixit 1970, v. 29).

Conclusion: Acceptance and critique of other philosophical systems in the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya

Like Haribhadra Virahāṅka, Yākinīputra is tolerant of other religious worldviews in the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya. His inclusion of a reworked, three-fold tantric system and adaptation of three, eight-fold, non-Jain yoga systems demonstrate his openness to the yogic paths found in other traditions.

Two specific verses suggest not only tolerance, but even universal acceptance of other religious truths:

The ultimate truth transcending all states of worldly existence and called nirvāṇa is essentially and necessarily one even if it be designated by different names.

It is this very entity that is designated by the words like Sadāśiva, Parabrahman, Siddhātman, Tathatā, etc. – words which have got the same meaning and a proper meaning at that (Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya v. 129-130, in Dixit 1970).

That being said, and like Haribhadra Virahāṅka, Haribhadra Yākinīputra also takes time in other parts of the text to critique other systems’ philosophical standpoints such as Buddhist notions of impermanence and Brahmanical monism from his own Jain position (cf. Dixit 1970, v. 193-203).

Are you interested in learning more about Jain Yoga? Complete a concentration in Yoga Studies in our remotely available MA – Engaged Jain Studies program, where you will learn all about the Jain Yoga tradition.

References

Dixit, K.K., translator. 1970. The Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya and Yogaviṃśika of Ācārya Haribhadrasūri. Ahmedabad: Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Bharatiya Sanskriti Vidyamandir.

Dundas, Paul. 2020. “Haribhadra”. In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Jainism. Cort, John E., Paul Dundas, Knut A. Jacobsen, and Kristi L. Wiley, editors. Leiden: Brill. Online.

Christopher Jain Miller, the co-founder and Vice President of Academic Affairs at Arihanta Institute, completed his PhD in the study of Religion at the University of California, Davis. His current research focuses on Modern Yoga and Engaged Jainism. Christopher is the author of a number of articles and book chapters concerned with Jainism and the practice of modern yoga.

In addition to the MA-Engaged Jain Studies graduate program, Professor Miller teaches several self-paced, online courses at Arihanta Institute, including:

- 1014 | Jainism, Veganism, and Engaged Religion

- 1008 | Jain Responses to Climate Change [Free Course!]

- 1006 | Jain Dharma and Animal Advocacy

- 1001 | Jain Philosophy in Daily Life